Medieval Byzantine Armors

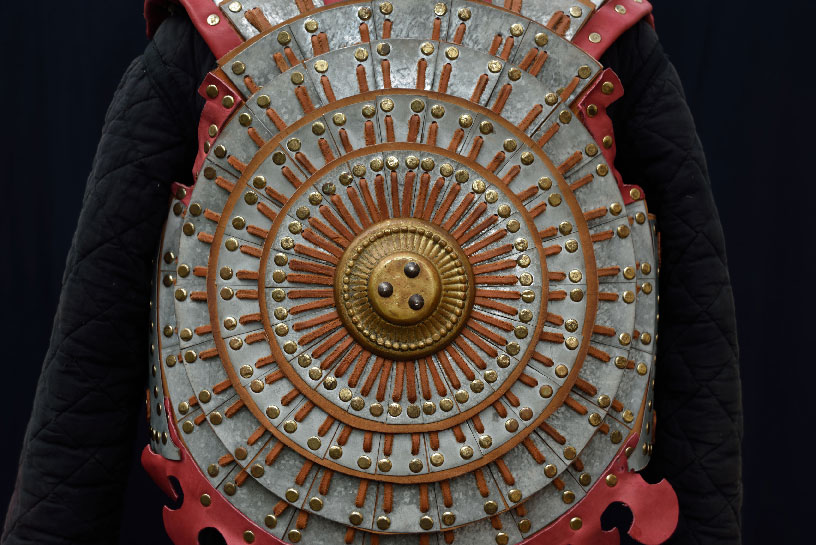

“Mirror” Armor of St. Theodore Tyron

late 13th AD

The study of medieval armors of the Eastern Roman Empire (9th – 15th century AD) is an exciting experience. As we said repeatedly, contemporary Greeks have ostentatiously forgotten this rich tradition of art even though they make eye contact with byzantine armors at a quasi-daily rate through church murals and icons. On this one, in the words of the author Katsikis Dimitri, chance is that it refers to a special armor typology of Late Byzantine period found exclusively in the peninsula of Haemus (from Serbia to Crete) and it can be considered as the most complex known armor in history from a perspective of design approach. One of the most characteristic painted representations of this typology is found in the Monastery of Protaton (Agion Oros) as the depicted defensive gear of St. Theodore of Tyron, within a mural crafted by hagiographer Emmanuel Panselinos (late 13th century AD). For reasons of convention we could call it “mirror” armor.

This armor protecting the body of the soldier of that time may well had been the highlight of Byzantine Military industry on soldier defensive gears. The thoracic portion consists of five concentric circles which overlap each other by half forming a pyramidal cross-section with five “steps” on top of which the smaller circle lies. These circles consist of a leather foundation on which it is pasted a sheet of metal (iron – bronze), fastened with rivets. These five components of the armor are connected with leather straps/cords maintaining to a large extent their kinetic freedom which gives the entire structure an attribute of a unique spring able to absorb and damp the kinetic energy of incoming projectiles. We should assume a corresponding provision for the dorsal part as well as six locking points, one on each armpit area and two pairs on the right and left area of the neck.

Such a design approach has not been observed in any other armor in the East or West through the centuries. It is a miracle of engineering genius and, in the words of the maker/artist Dimitris Katsikis, it is the most important equipment that has been reconstructed as it opened a new window for a historical period that is ostentatiously ignored. Academic “exploitation” of Byzantine armor could well give a new impetus to Byzantine studies especially in sections relating to military affairs. Unfortunately Museology in Greece is not yet ready to accept and bring such cultural goods presenting a considerable lag to its western countries’ counterpart.