Ancient Greek Armors

Αthena’s helmet

5th century B.C

The Corinthian helmet is the most iconic defensive gear of classical antiquity. Pictorial

representations during the Archaic and Classical period are ubiquitous and encountered in every

means of artistic expression: sculptures, vase paintings (especially portrayed on Corinthian vases),

frescoes, literature etc. Corinthian helmets begin to make their appearance during to first quarter of

the 7th century BC and continue to develop for the next three hundred years until they go out of

fashion after the collapse of the conservative Greek city states at the end of the 5th century BC.

During the Persian Wars (490-479 BC) its popularity was extremely high and thousands were made

all over the Greek world. The name derives from the city of Corinth (despite the fact that its actual

origin is ascribed to the local workshops of the city of Argos).

The historian Herodotus considers it already as something “antiquated” (Hrd, Histories. iv 180) a

fact which is indicative of its long usage during the past centuries. The Corinthian helmet, as with

the muscled cuirass, should be considered as an indigenous Greek metal working innovation

gradually becoming the most widespread characteristic type of Greek defence gear. It was

commonly raised by a single piece of bronze sheet hammered onto a stone dome although during its

early evolution stages (early Archaic period, proto-Corinthian helmets) more complicated

cast/soldering techniques were applied as well. Covering the entire face and leaving visible only the

eyes and mouth it was designed to provide the maximum protection for a warrior’s head within a

very cohesive battle formation – the phalanx.

The main technical characteristics of the Corinthian helm are the curved profile of the top, the

pointed nasal, the almond-like eye openings and the broad protruding cheek covers (paragnathides).

To protect the warrior’s skull the interior was well padded with wool, sponges, leather and fabric. It

was usually popular to add decorative stylized crests (lophos) of colorful horsehair plumes often

running vertically from front to back, a practice which accorded them a more distinct identity and

individuality.

During its latter stages of development more elaborate lighter versions were produced with the

shape extended to resemble a gigantic human phallus. Given the Corinthian helmets’ iconic status

as the signature of the hoplite phalanges which faced the huge Persian invading armies at Marathon,

Thermopylae and Plataiae, it is not surprising that the goddess Athena and the famous Athenian

politician Pericles were frequently depicted wearing the same helm perched over the forehead.

Statistically the Corinthian helmet was depicted on more heroic sculptures than any other

contemporary helmet because the Greeks inevitably associated it with the glorious past. It should

also be stressed that a custom-made Corinthian helmet for a young man in Greek culture was not a

mundane affair as would be the purchasing of any piece of equipment, but signified the passage to

manhood and his acceptance as a civilian of the demos when it was fitted for his first time. We have

to presume, therefore, that helmets occupied a place of honour in a hoplite’s home.

Description

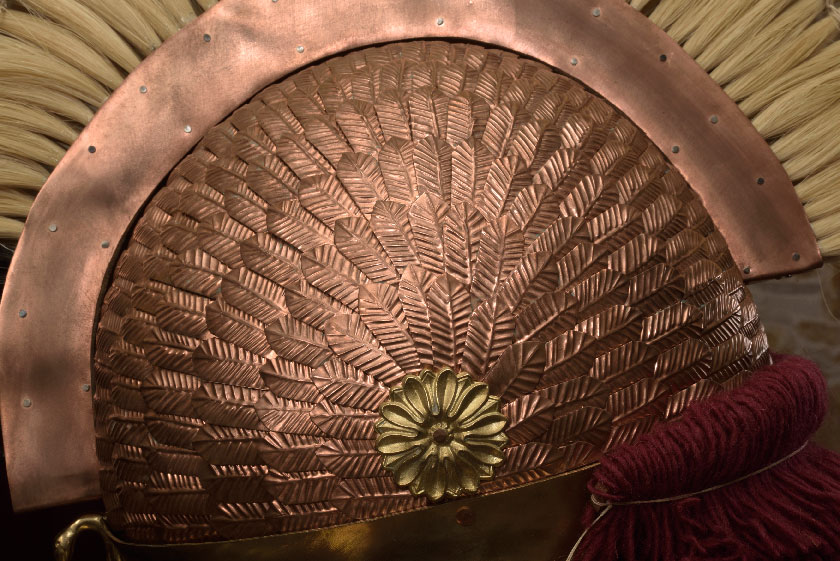

Most probably the most intriguing version of Corinthian helmet is the scaled helmet. It was usually

depicted on red figure pottery paintings and is actually a modified model of the original, its major

difference being the covering of the dome with hundreds of tiny scales. Scaling in Greek school of

armouring was a widely accepted practice and we can spot scaled guards almost everywhere in

many typologies and arrangements. Artisans integrated this specific element to a helmet’s overall

design creating a luxurious and extravagant distinctive identity.

The reconstructed helmet has been based on a red figure vase painting (dated to the second half of

the 5th century BC). It retains all the typical technical features of a Corinthian helmet mentioned

above. The mask was made from a hammered bronze sheet; the dome was covered by 180 bronze

pointed ridged scales and 180 copper leaf-like scales, directly riveted to the top, producing an

astonishing optical result (the left side with bronze and the right side with copper elements).

The usage of different type of scales in the same piece of equipment is attested in various pictorial

archaelogical findings. A detachable crest with wooden base and natural horse hairs (mainly white

with a black tuft at it’s back end) have been fixed on the top of the roof. The lateral walls of the

wooden base have been lined with copper and bronze. Each of the cheek’s base are strongly

attached to the main body of the helmet with a horizontal hinge (strofeis in Greek) a technical

arrangement which allows vertical mobility. Each side of the mask has ear openings – a later

development as early helms were completely enclosed. A red woolen fringe covers the front of the

helmet and a duck-like hook of cast bronze has been riveted on the back at the nape (a suspension

point). All the inner surfaces have been lined with wool and linen.

The end result is a valuable hand-made artifact which incorporates a range of traditional techniques,

precious natural materials combining high classical aesthetics, luxury and prestige.